Speech vs. Song

George List's Boundaries of Speech and Song

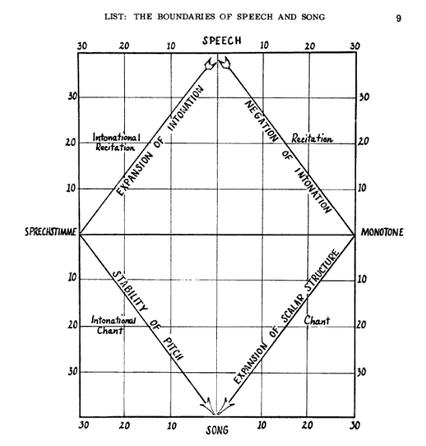

This system is an excellent, if somewhat awkward method of analyzing pieces of folklore, art, and oral literature as to where they fall between speech and song. It does not give us a concrete answer, (although by some interpretations crossing the x axis gives an answer) but a set of informative and qualitative coordinates using two sets of opposites and connecting them directionally across two paths.

At the top and bottom of the Y axis are the opposites we aim to analyze, and on the left and right are two other intermediary opposites that can help us analyze those on the Y axis. On the left is a type of speech called sprechstimme, which is a theatrical manner of speech-like voice with exaggerated highs and lows of pitch and volume without firm tonality or pitch stability. On the opposite end is monotone, a manner of speech inflexible in pitch and inflection. The chart demonstrates two possible paths from speech to song, one leading through sprechstimme and the other leading through monotone. The left path begins by expanding intonation from speech to sprechstimme and then to song by stabilizing pitch. The right path leads from speech to monotone by negating intonation, and then to song by expansion of scalar structure.

Much of Fanbai revolves around pentatonic-style scales popular in much of Chinese folk music. These are five note scales, the most common of which, the major pentatonic scale, is made up of notes 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6 of the western classical major scale. This scale typically sounds very amicable and even, with less drive towards the tonic (home) note and less opportunity for dissonance and tension than the typical western major scale. Fanbai is monophonic, consisting of one line only sans accompaniment (aside from non-melodic percussion such as cymbals), chords, or harmony. This, plus the amicability of the scale, make Fanbai very easy to improvise and memorize. Fanbai, while it shares a general tonality with Chinese folk music in general, it is significantly more restrained in rhythm, range, and dynamic range (volume) than folk music with group chant such as praises, gathas, and some sutras being even more restrained than free chant. Fanbai also commonly uses small glissando, sliding between pitches instead of moving between them distinctly, giving it slightly less stability of pitch than some other forms of speech/song.

List puts intonational chant along the left path on approximately (20, 10) in the southwestern quadrant and chant in the same coordinates of the southeastern quadrant. I estimate that Fanbai shares qualities of both these types, and falls somewhere between them and farther down towards song at around (30, 0) in the southern half directly between the two paths as it both has fairly stable pitch and a very stable if simple scalar structure. This puts it closer to song than most types of chant while still retaining some of their qualities.

This closeness to song to me represents Chinese Mahayana Buddhism's interest in the third of Mabbet's relationships, as free chant in particular represents a connection to the scripture and by extension the divine that is more personal and emotional. This can be seen even further in certain centers of practice which have begun to embrace more westernized and popularized types of Buddhist music which fall firmly into the song category.

Chant as a memorization technique also aligns with Mabbet's second relationship. This can be seen in the fact that Fanbai is more restrained than most Chinese folk music.

Mabbet's first relationship can even be found in the ritual value of chant, although this is more important in the Sangha's relationship with the lay population, especially rural populations which hold more stock in ritual and mysticism.

Analysis through a combination of these two techniques help draw conclusions about which aspects of chant appeal to which aspects of religion, culture, and music.